The Intricacies of the Bench Press

(A Physio’s Perspective)

DISCLAIMER

What follows, is perhaps an unnecessarily deep-ish dive into the biomechanics of the bench press.

If you’re at risk of paralysis by analysis – just turn back now and go bench!

Ah, the bench press. A bar, a bench, and a press. You control the bar down, you press it up. Simples, no?

Well, like most things in life it can be simple, but it can also be quite complex. I like complex, but only when it eventually feels simple! The following is my attempt at breaking down the complex.

The Bench Press

There are three main movements occurring in a bench press:

Shoulder Flexion (Mainly Front Delts Working)

Shoulder Horizontal Flexion (Mainly Pecs Working)

Elbow Extension (Mainly Triceps Working)

Shoulder Flexion

Shoulder flexion demands are determined by the distance of the bar in front of the shoulder joint.

The further in front of the joint, the harder the lift is for your shoulder flexors (front delts specifically, and upper pecs to a lesser degree) – see below:

When compared to the second image, the first image is greater effort on your front delts.

Shoulder Horizontal Flexion

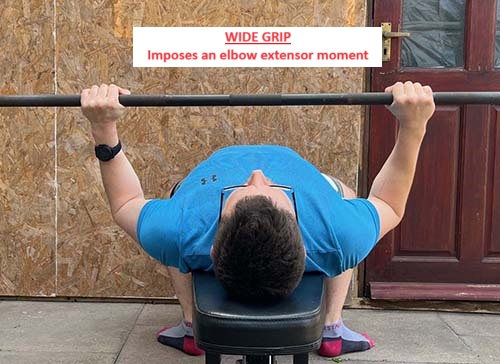

Grip width determines the horizontal flexion demands. The wider the grip, the greater lateral distance between your hand and shoulder. This wider grip will place greater demands on the pecs (responsible for horizontal flexion). See below:

Now your triceps extend your elbows. They also allow you to impart lateral forces on the bar, thus aiding your pecs (responsible for horizontal flexion) substantially as well. This is explained in slightly more depth towards the end of the article.

As the triceps can help to drive the bar backwards towards your shoulders after touching your chest, they can help the front delts (shoulder flexion) too.

Remember, shoulder flexion demands depend on how far the bar is in front of your shoulders (when looking at it from the side).

When the bar is on your chest (as far in front of your shoulders as it’ll be at any point in the lift), shoulder flexion demands peak.

The shoulder flexion demands decrease throughout the lift as the bar drifts back over your shoulders, until the bar is directly over your shoulder joint at lockout and shoulder flexion demands are negligible.

In theory then, one could assume that benching straight up and down would be the most efficient bar path – that is touching the bar super high on your chest. This would pretty much eliminate all shoulder flexion demands, BUT it significantly increases range of motion on the shoulder joint (as it has to flex further when the bar is at its lowest point) whilst it’s under load. The addition of horizontal flexion, with internal rotation is also asking for some nasty Acromioclavicular Joint Impingement.

DRIVE THE BAR UP AND BACK

So that cue of drive the bar UP and BACK towards your throat actually reduces the demand on shoulder flexion (controlled by the front delts), whilst not affecting the demands on either horizontal flexion or elbow extension.

Most elite lifters utilize the bar path (up and back, then straight up), whereas most novice lifters drive the bar straight up initially, then up and back to lock out. See the Stronger By Science article here for a deeper dive into this rabbit hole. Grip width doesn’t necessarily have to affect shoulder flexion demands in theory, but it generally does in practice. Most people touch the bar a bit lower on their chest when they bench with a close grip, increasing shoulder flexion demands. However, since people also tend to load up less with a closer grip, the effect is offset slightly, but it’s likely not negated entirely.

Elbow Extension

The further your elbows are in front of the bar, the higher the elbow extension demands. That is to say the closer your elbows are to your legs whilst maintaining the bar over the chest, greater stress will be placed on triceps to extend.

If your elbows fall directly under the bar (when looking from a side on view), the less stress will be placed upon them during elbow extension (which can be seen in the first image).

Now Here Comes the Sticky Wicket!

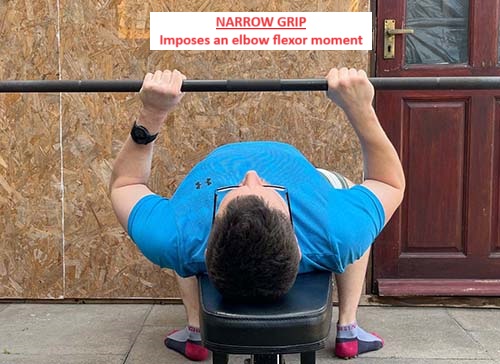

Remember those flexor vs extensor moments? Well, your grip width determines whether the bar imposes a flexor or extensor moment at the elbow!

A wide grip = hands resting slightly outside the elbows. This imposes an elbow extensor moment.

A narrow grip = hands resting inside of the elbows. This imposes an elbow flexor moment.

Outward Lateral Forces

What on earth are outward lateral forces you ask? Well, one way to visualise this is to firstly understand that on a barbell you CAN apply outward lateral forces, in addition to pressing up. With the Dumbbell (DB) press you have to apply force straight up (whilst the weight stays pretty much right over your elbow the whole time).

So let us think a little more about what happens with a DB press, then hopefully this topic will be a bit clearer than mud!

If the DBs are closer together than your elbows are at the bottom of the DB Press, it’s harder on the triceps – as can be seen in a Tate Press. If the DBs are further away from each other at the bottom of the lift than your elbows are from each other, it stresses your pecs more – as can be seen in the Chest Fly.

With a DB press your elbows naturally want to move further apart as you lower the weights, and you naturally keep your hands over your elbows so the weights move further apart as well. You then reverse the motion on the way up.

Moving the DBs straight up and down instead of in an arcing movement feels odd because it doesn’t allow the weights to stay over your elbows.

The reason your elbows have to stay pretty much under the weight when you’re DB pressing is that you can’t impose a meaningful amount of outward lateral forces on the dumbbell. You would just throw them off to the side if you did. That’s why you have to apply force straight up through the DBs.

Because you can’t impose that outward lateral force with your triceps on a DB press, you can’t get your triceps involved in the DB press as much as you can on a barbell bench press (where the triceps can apply those outward lateral forces, in addition to pure elbow extension).

If your elbows are pointed out (think Tate Press), then when your triceps contract, they’re mainly imposing lateral forces on the weight on the way up.

All this ultimately means that muscle activation in the pecs is the same in both DB and Barbell Bench Press, but triceps activation is lower in the DB press.

PHEW!

OKAAAY. Flipping heck, stay with me with here 😊 This is where we need to draw on physics again, and boy that’s a struggle for someone like me who may have misloaded a squat PB, or two, in the past! #poorplatemaths

So why are outward lateral forces important in the barbell bench press?!

Well, in my article about moment arms I mentioned that the downward linear force on a 180kg barbell bench press is 9.8m/sec2 due to gravity (i.e. gravity is pulling the bar straight down).

Now we know about lateral forces, this changes things a bit. When we add lateral forces into the picture, the resultant force vector (this being the product of two forces in different directions, which in the image below is F cos 0 + F sin 0) won’t be pointing straight down.

On a bench press, we press up AND laterally. See below:

Remember – the external moment arm is the perpendicular distance between the joint being acted upon and the vector of force application.

In the image above we can see that the resultant force vector (when accounting for lateral forces) passes much closer to the shoulder than the force vector for gravity alone (i.e. straight down to the ground).

Newton’s 3rd Law (every action has an equal and opposite reaction) means that the forces are being transmitted through the scapular plane of movement as a result of the addition of outward lateral force applied to the bar. This all means that the resultant moment arm for horizontal flexion is shorter, making the lift easier on your pecs.

On the left is the shoulder horizontal flexion moment arm (solid black) when only accounting for vertical forces.

On the right, you can see how much shorter the horizontal flexion moment arm becomes when accounting for horizontal/lateral forces on the bar.

Because your hands don’t move on the bar, the pecs and the triceps work synergistically at both the elbow and shoulder:

- The pecs help the triceps extend the elbow.

- The triceps help the pecs horizontally flex the shoulder.

Since the forearm can’t move much because the hand position is fixed, the shoulder has to horizontally flex as your triceps work to extend the elbow.

The opposite is true with the pecs: since the hands are locked in place on the bar, as your pecs work to horizontally flex the shoulder, the elbows have to extend as well.

So in the barbell bench press, stronger pecs make it easier to extend your elbows, and stronger triceps make it easier to horizontally flex your shoulder.

Grip Width

Elbow extension demands are greater with a closer grip.

If you use a shoulder-width grip, your elbows will be outside your hands through most of the lift – this means there’s an external elbow flexion moment throughout most of the press.

If you use a wide grip, your elbows will never be outside your hands, so there will actually be an external elbow extension moment through most of the lift.

Hence, why close grip bench is more challenging on the triceps, and wide grip bench is more challenging on the pecs.

Tucking Elbows

The degree to which you tuck your elbows will impact elbow extension demands as well.

As long as your elbows stay under the bar, tucking more decreases elbow extension demands (as your elbows move in toward your shoulders and away from the plates).

This technique can however help you drive the bar back up off your chest, allowing your triceps to help out your shoulders. This is fine, as long as you make sure to flare your elbows to get them back under the bar by midrange of the press. See Greg Nuckols demonstrating this below:

The top is acceptable: elbows slightly in front of the bar at the bottom (helping to drive the bar back up off the chest), getting back under the bar through the midrange.

The bottom is what you DON’T want to happen: elbows start in front of the bar and stay in front of the bar.

Similar to shoulder flexion demands, elbow extension demands change throughout the range of motion.

The elbows generally move OUT (away from the shoulders, toward the plates) laterally as your upper arms (biceps/triceps) approach parallel to the floor, when both lowering the bar and pressing the bar,.

The elbows generally move IN (toward the shoulders, and away from the plates) laterally as your upper arms (biceps/triceps) get further from parallel to the floor.

Because of that, elbow extension demands are the highest when your upper arms are roughly parallel to the floor. That’s most likely the reason why most peoples sticking point occurs when their upper arms are roughly parallel to the floor.

Now two things we haven’t covered yet are: that controversial arch, and leg drive. I may explore these in greater depth in another article – but for now… the arch simply reduces the range of movement that bar that has to travel during the lift. Leg drive can help to provide more power on the upward phase – the amount of power, and whether this significantly helps a lifter, depends on the position on their feet and the biomechanics of the lifters hips/knees/ankles.

And that, my friends, is a whistle stop tour of the biomechanics of a bench press! I would urge you to head over to the Stronger By Science website if you want to geek out even more! 🙂

References

Online Math Learning (2024) Online Math Learning. Available at: https://www.onlinemathlearning.com/resultant-forces.html (Accessed 01/07/2024).

Greg Nuckols (no date) Stronger By Science. Available at: https://www.strongerbyscience.com/how-to-bench/ (Accessed 01/07/2024).

Whilst not writing for FGUK, Tim works as a Physiotherapist, Personal Trainer and is a Retired Ammunition Technician with the British Army. In his spare time Tim enjoys engaging in a whole variety of sports, spending considerable time with his little rascal of a dog, relaxing with his friends and family, but most of all.. geeking out on all things fitness!